Doing the once unthinkable: visiting a South American shantytown alone at night

Narco battlegrounds have become dance-floors in Colombia’s most famous barrio

NOT FOR the first time in my life, I’m doing something that seemingly defies common sense.

It’s 8:45pm, and I’m ascending the steep, meandering hills of Comuna 13 in Medellín, Colombia. My calves pulsate.

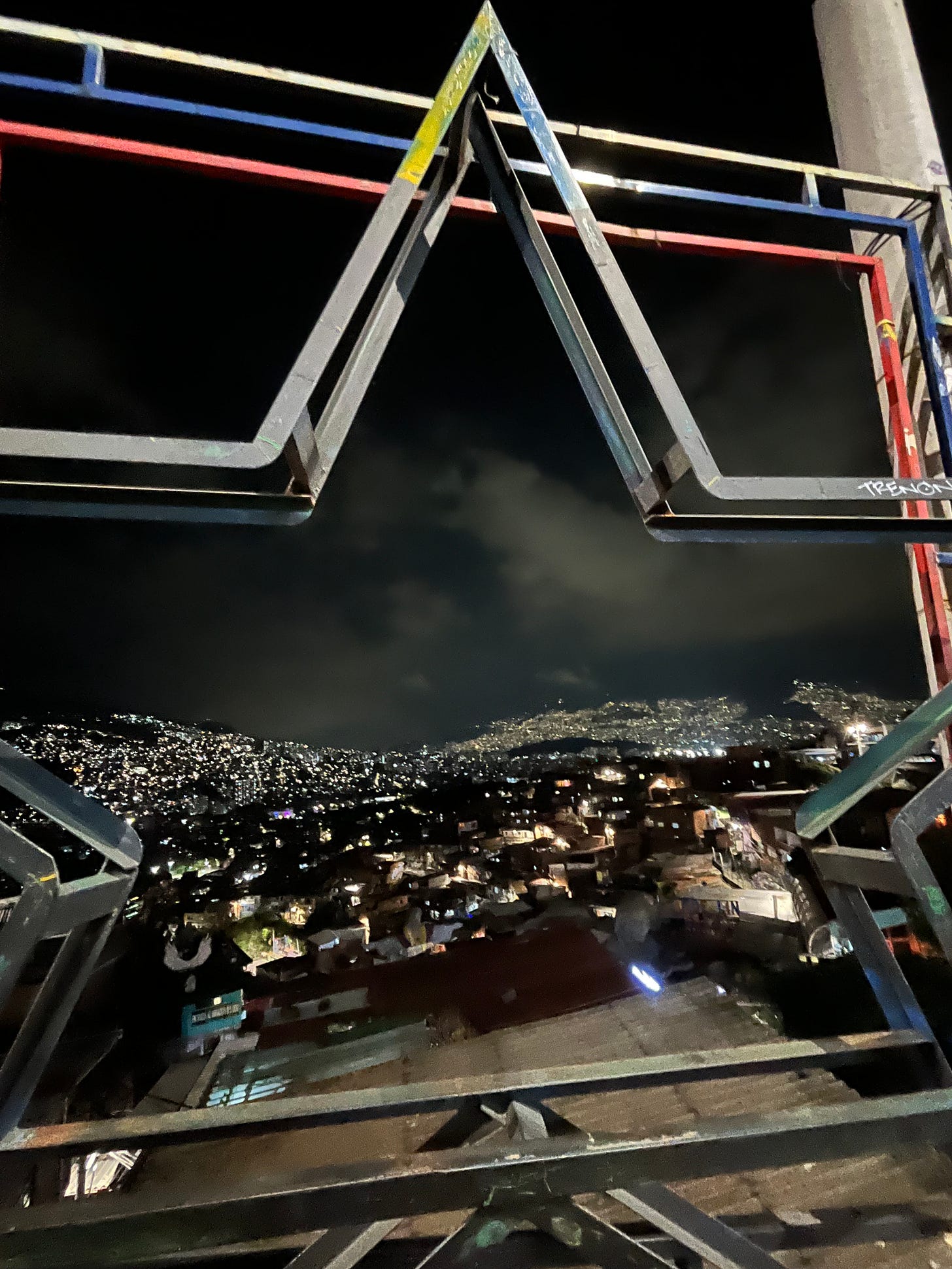

Lights from closely-stacked mountain homes twinkle like a million pierced ceramic lamps.

Eyes follow me on the winding street, shared harmoniously with howling dogs, growling motorbikes, smoking teens and playing kids.

It’s the only shantytown-like neighbourhood in Latin America - if not the world - where I’d do this solo after dark. Most of Rio’s favelas or Buenos Aires’s villas miserias (‘misery towns’) are no-go zones.

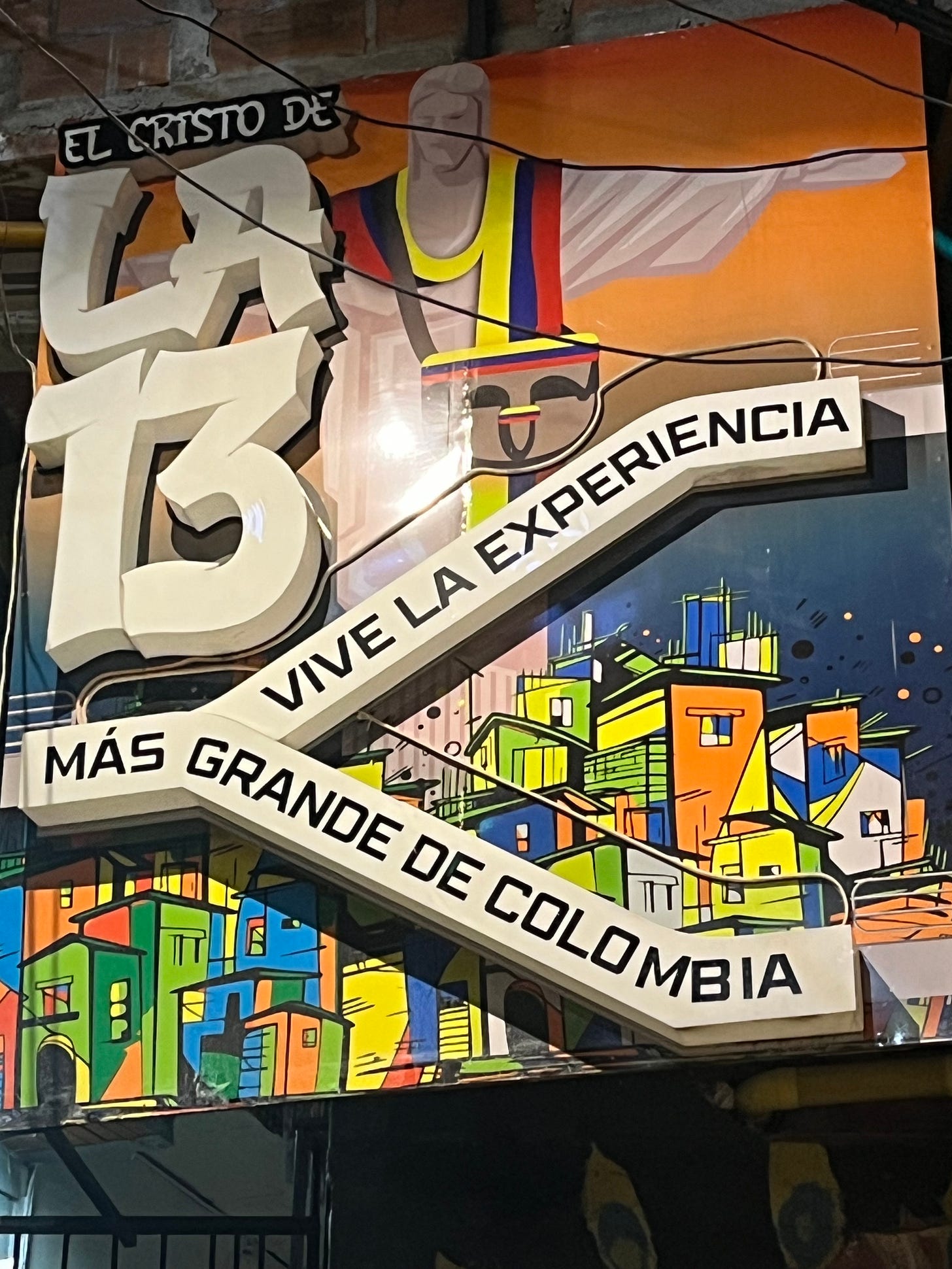

Comuna 13, though, is now Medellín’s most visited tourist attraction. Shops sell t-shirts emblazoned with Pablo Escobar’s face - a reminder of who once ruled these streets.

This is a reader-supported publication. Consider a paid subscription here

His inescapable image still divides. It’s curious people purchase merchandise glorifying someone who murdered over 4,000 - from journalists to presidential candidates. Others say Escobar - once among the world’s richest men - built hospitals and schools for Medellín’s poorest (albeit to curry favour).

That merch may soon vanish. This year, Colombian Congress proposed a bill banning Escobar-related memorabilia that “insult victims.” Comuna 13 vendors pushed back, fearing for their livelihoods. Wordplay on a nearby bar reflects the city’s resolve to shed its violent narco reputation: ‘The Beyond EscoBar.’ In the comuna’s signature vibrant palette, each letter is a different colour.

Higher up, cosier multi-coloured bars with astonishing mountainside views subversively make the lurid aesthetically pleasing.

Today, replacing bullets, the bangs come from beats. Reggaeton and rap by Medellín’s newer icons - Karol G and Maluma - play as I wind up, echoing the city’s newfound cultural confidence.

I reach the iconic orange-roofed 384m-long escalators, completed in 2011 to connect hillside residents with the city below. A 35-minute hike now takes six, thanks to six sections that also boost tourist flow. As I step onto section two, feeling similar reverse-vertigo as when alighting the tube at Angel, I’m too busy looking up to notice who’s behind me.

“Do you like the rap?” asks a man with bloodshot eyes and a portable beatbox on his shoulder. I nod nervously. “Where you from?” “Londres,” I say. He rhymes it in Spanish with five couplets. I’m impressed. For five escalators, he stands on the steadily ascending step below me, freestyling about everything from aguardiente (aniseed liquor) to a final, poignant line: “Medellín isn’t all about Escobar, it’s all about art.” I tip him - he’s one of the comuna’s ‘rappers for peace.’ Some kids see my wallet. “You will buy me soda!” one says, but it’s the only time I’m asked for money in what’s otherwise a peaceful climb.

Three days ago I joined a daytime guided tour with Juan, a local who introduced us to his aunt’s restaurant for crunchy plantain snacks. He taught us how residents reclaimed their ‘barrio bajo’ (‘low class neighbourhood’) from violence through creativity. They began lifting themselves from poverty and depression using the power of art and optimism. Displacement, kidnappings and murder have, largely, been replaced by street dance, peaceful hip hop, graffiti art and sculpture. Former battlegrounds are now dancefloors.

The tour bursts to life with a dance troupe: seven ripped men and one strong woman breakdance to Dizzee Rascal on a basketball court. They display gravity-defying contortions - tumble turns, one-arm handstands, head-spins. The crowd, many fellow British or American digital nomads, tip generously. Many, like me, were lured knowing the 2016 peace deal between the government and guerillas ended 52 years of civil war, and that today’s innovative Medellín is the realisation of successive visionary mayors rebranding it as a remote-worker hub. Not everyone’s thrilled: in 2023, irate outpriced locals in wealthier suburbs flyered lampposts with “Gentrifyer GO HOME.” But Comuna 13’s vibe is the opposite. Residents sell tours, trinkets, stories, and - in a genius stroke - Instagram ops with photogenic sculptures: a Colombian-flag-draped Christ the Redeemer; a giant gorilla; outstretched hands. Lines of influencers form.

Then we see the murals: covering every surface from tunnels to rooftops from fluorescent to portraiture. Much is political; one depicts Operation Orion, when in October 2002 the government stormed the comuna, killing suspected cartel members and civilians alike. “The escalators were an apology,” Juan says. Together with a sprawling cable car network, they make Comuna 13 the world’s most accessible hillside slum. “We’re not a slum anymore,” Juan says. “We’re a global attraction.”

We’re each handed two signature Comuna 13 items. First, a mango icepop dipped in salt and herbs, to refresh us. Second, a spraycan to inspire us. I, unoriginally, write “Gazz” on a communal graffiti wall.

This is a reader-supported publication. Consider a paid subscription here

It’s Juan who convinced me it was safe to return solo at night - unthinkable three decades ago when Medellín was the world’s most dangerous city. As I summit the meandering narrow street, smells of cooked meat and petrol juxtapose with the freshness of the air this high.

Nowhere on earth resembles Medellín. Puffed, I gaze through stencilled stars and bold-letter art framing the valley’s opposite mountains, resplendent with trees, homes, lights and fresh hope. Once isolated, this transformed comuna now whispers to the world: come. Witness our resurrection.

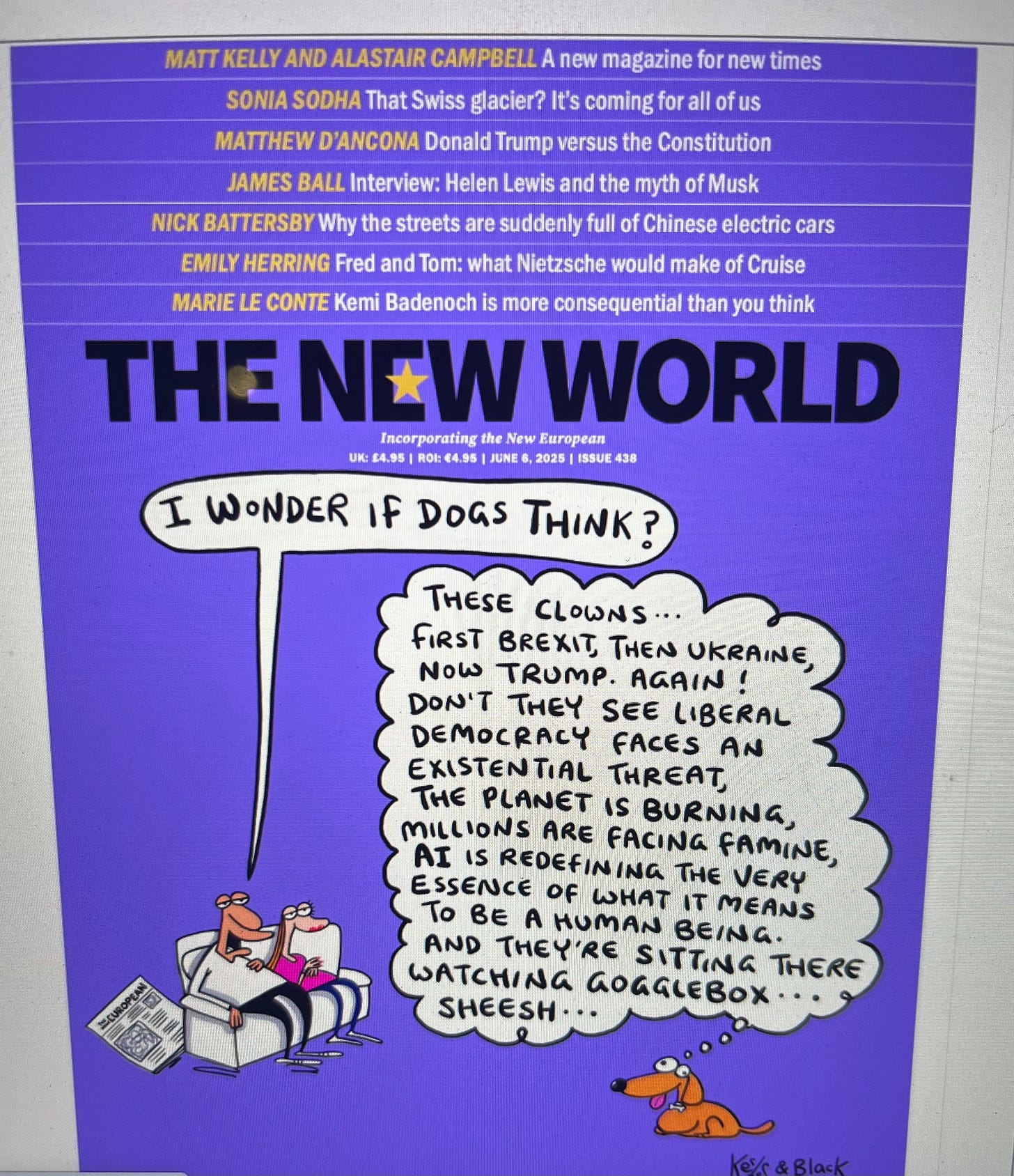

A shorter version of this story appears in the current edition of The New World (formerly The New European) https://www.thenewworld.co.uk/gary-nunn-the-colombian-shantytown-where-escobar-was-king/

Subscribe to The New World: https://www.thenewworld.co.uk/join/